Phase 4: Implement, Monitor, Evaluate, and Adjust

The content presented here is a simplified version of the Adaptation Planning Guide. For the detailed full text, download the Phase 4: Implement, Monitor, Evaluate, and Adjust chapter.

Phase 4: Implement, Monitor, Evaluate, and Adjust ChapterExplore resources in Adaptation Clearinghouse Database

Phase 4: Implement, Monitor, Evaluate, and Adjust ResourcesDownload list of citations

APG EndnotesIn Phase 3, the project team and community built an adaptation framework of the community’s vision, goals, and priority adaptation strategies. Phase 4 uses the adaptation framework to prepare an implementation program.

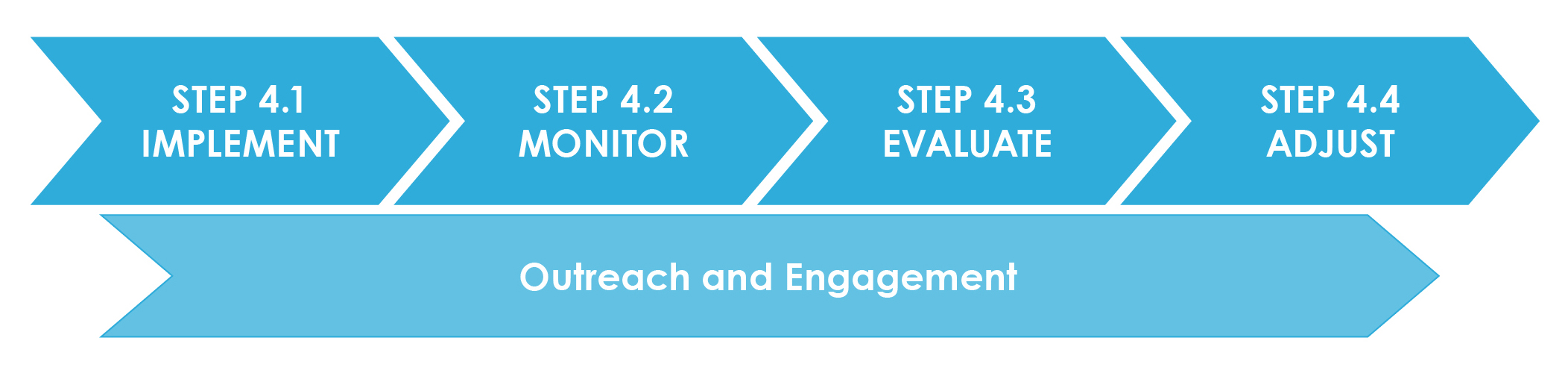

This section summarizes the most important step of adaptation planning, implementation. To ensure that implementation of each strategy is effective and continues to be effective, communities should monitor, evaluate, and modify strategies as needed based on their observed effectiveness, local changes, and new science. This section divides the Phase 4 process into four steps, shown in Figure 17.

- Prepare an implementation program to put adaptation strategies into action.

- Create a monitoring program to track implementation and ensure the monitoring program can be adjusted as needed.

- Establish an evaluation processes to assess how well and how long the vulnerability assessment and adaptation strategies serve the community; ensure that the evaluation process can be adjusted as necessary.

- Adjust adaptation strategies as monitoring and evaluation input is received.

Community and Stakeholder Engagement in Phase 4

Long-term implementation cannot be effective without close collaboration with the community. Outreach and engagement should be conducted through all phases of adaptation planning and should continue through implementation. Beginning with the scoping of the adaptation planning efforts (Phase 1) and continuing with the vulnerability assessment (Phase 2) and development of strategies (Phase 3), close collaboration bolsters community understanding and support for implementation. Implementation should actively and meaningfully involve community members and provide transparency in the monitoring and evaluation of effectiveness. This is particularly important in frontline communities who are disproportionately vulnerable to climate change, including tribal communities. This ensures that community members are partners if the results of monitoring and evaluation require a change in adaptation strategy. Involving the same representative groups formed during the previous phases can help with this objective.

In all the phases, equity is a critical component of these efforts. This means including opportunities for meaningful involvement from members of frontline communities and vulnerable populations who are disproportionately impacted by climate change and often underrepresented in community decision-making processes. Tribal communities are also often underrepresented in local government processes and should be intentionally engaged or partnered with, especially when a project impacts tribal resources. (Note: If the plan or project resulting from the adaptation process is a General Plan Amendment or otherwise subject to the California Environmental Quality Act, the lead agency must follow state regulations for tribal consultation and assessment of potential impacts to cultural resources as early as possible in the project.) It is important to rely on frontline, vulnerable, and tribal community representatives for their local expertise and to determine adaptation planning strategies and implementation options.

When community members understand the frequency and severity of climate- related hazards is linked to the effectiveness of GHG reduction and climate change adaptation strategies, it prepares them for the necessity of adjusting approaches to adaptation over time. Fostering this understanding and including the groups formed in assessing monitoring data and choosing next steps is critical to ongoing effectiveness. Each step of Phase 4 incorporates outreach and provides a list of sample actions. These outreach actions are primarily taken from the Guide to Equitable Community-Driven Climate Preparedness Planning by the Urban Sustainability Directors Network.

Step 4.1: Implement

In Phase 1, Step 1.1, the project team identified the end product or plan of the adaptation planning process. Phase 1 also presented the types of plans, programs, and implementation mechanisms common in adaptation planning. In Phase 3, the project team developed and prioritized adaptation strategies. Development of adaptation strategies likely included identification of a potential lead department and/or partners tasked to implement a strategy, a time frame for implementation, and potential cost estimates. When starting Phase 4 and implementation, the first step is to prepare an implementation program and to confirm the implementation mechanism and responsible department of entity needed for each adaptation strategy. Some strategies will be implemented upon adoption of the plan prepared as a result of the adaptation planning process, while others will need to be further developed and/or be integrated into other plans or programs.

All adaptation strategies have temporal components that include time to implementation, timing of necessary action, and duration of effectiveness. These elements of time must be considered for all strategies and when devising the method of measure delivery.

For implementation strategies that will be further developed or implemented, the team should identify the planning document or other mechanism best suited to drive strategy implementation, as well as any documents that should be amended to ensure consistency. The answers to two questions can help clarify the choice of mechanism:

- Which mechanism most closely overlaps the intent and topic area of a strategy?

- Which mechanism is next slated for update or revision?

Regardless of how they are implemented, adaptation strategies tend to be in more than one plan, such as the general plan, local hazard mitigation plan (LHMP), climate action or sustainability plan, integrated regional water management plan, and capital investment plan. Other possible mechanisms for adaptation strategies are discussed in Phase 1.

- General plans

- The land use element

- The circulation element

- The housing element

- The conservation and open space elements

- The air quality element

- The environmental justice element

- Local hazard mitigation plans

- Climate action plans/sustainability plans

- Integrated regional water management plans

- Capital improvement planning

Adaptation strategies, regardless of the plan or program that contains them, need to be implemented to achieve their intended outcome. This requires assigning staff, developing programs or other measures, securing funding, and engaging the public. Many of these choices are described in Phase 3. It is important to confirm the remaining details to implement the strategy. This process builds on the prioritization of adaptation needs and strategies in previous phases, and outreach and funding are covered in subsequent sections. The way to implement adaptation actions will vary by location and jurisdictional context. Things to consider when developing the implementation approach are:6, 7

- Build on existing processes

- Assess cost-effectiveness

- Leverage community and private sector alliances

- Establish partnerships regionally

Implementation outreach

When the adaptation planning is complete and the plan is approved, the transition to implementation can be celebrated with a fun, public event. Such an event is an opportunity to honor stakeholders and their role in the process and is the next step of implementation. The event should be planned with those already engaged in the process, but this is also an opportunity to identify stakeholders that have not been involved and could be important voices and partners during implementation. This includes communities most likely impacted by one or more points of vulnerability or affected by the strategies that have been prioritized for implementation.

Implementation strategies can and should build on the actions recommended in Phase 3. In this case, rather than asking community members to help brainstorm adaptation measures, community members can be asked for help supporting and bolstering implementation and supporting monitoring. During engagement, the project team can share ongoing progress of adaptation actions and their resulting benefits. Communities can be sought in the following roles:

- Collaborators in education.

- Participants and facilitators of tours of adaptation projects as they are implemented.

- Recipients of surveys to assess effectiveness and social acceptance.

- Receptors or generators of online updates of adaptation progress.

- Participants or leaders of pop-up booths at locations illustrating adaptive action or community events.

Communities can ensure ongoing support for adaptation by maintaining outreach efforts. Climate adaptation requires ongoing, long-term commitment despite the changes in elected leaders. When people are informed about and involved in adaptation strategy development, implementation, and monitoring, they are more likely to call on local leadership to continue support for that. In the best cases, local agency staff and local organizations are partners during the implementation process.

Implementation funding

Strategies must be funded regardless of how they are implemented, or the planning mechanisms used. Funding and financing sources can include local general funds, bonds, taxes, assessments, fees, grants, private sector partnerships or investments, non-profit grants and partnerships, among others. The state has many grant programs to support location adaptation actions funded through cap-and-trade. The Adaptation Clearinghouse’s “Investing in Adaptation” web page lists many funding opportunities by adaptation sector and has guidance on conducting fiscal analyses of adaptation strategies.14 It is regularly updated as funding sources evolve. The California State Library also lists funding opportunities resulting from recent legislation.15 Climate Adaptation Finance and Investment in California also has guidance on funding adaptation measures intended for local government staff. The Regional Resilience Toolkit includes steps for identifying and gathering adaptation funding sources.16 Some federal sources, such as FEMA’s Hazard Mitigation Grant Funding (HMGP) and Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities (BRIC) programs can be used to fund and finance adaptation actions. Many communities across California have historically used federal funding for these activities. Non-profit funding sources may also be available.

Local agencies often rely on their general fund for partial or full funding of implementation since they control it and using it does not rely on local ability to receive grant funding or raise new capital. However, local agencies often have limited general funds and competing needs for its use.

In cases where a community does not have general funds, staff, or other funding resources to implement all adaptation strategies, it can be helpful to rank strategies by how important it is to enhancing climate resilience and by the local capacity to fiscally support implementation (refer to Task 1.2). Strategies can be classified based on whether current support of a strategy would require 1) no budget adjustment, 2) reallocation of funds, or 3) new and/or external funding.

OPR’s Climate Adaptation Finance and Investment in California includes a chapter on funding and financing implementation with guidance for local governments regarding options for bonds and taxes. It also includes grant programs by sector. It is intended to provide a survey of issues, considerations and sources of funding that can help guide strategies and tactics for investing in adaptation and resilience in California.20

In times of economic downturn or limited local budget, collaboration with regional partners can result in joint planning and resource sharing activities, as well as cooperative purchasing agreements to support implementation. The Alliance of Regional Collaboratives for Climate Adaptation (ARCCA) provides ways for communities in many parts of the state to collaborate, limit costs, and achieve effective adaptation measure development and implementation.

AECOM partnered with Resources Legacy Fund to produce Paying for Climate Adaptation in California: A Primer for Practitioners, a report that synthesizes information local decision-makers need when thinking about funding and financing climate adaptation. The report offers a foundational understanding of existing constraints and opportunities and recommends ways cities, counties, water districts, utilities, state agencies, private companies, and other entities can make adaptation and resilience investments.21 The AECOM report categorizes funding opportunities into:

- Grants and assessments

- Taxes

- Fees

- Private involvement

Resources such as Blue Forest Conservation’s Forest Resilience Bond, the CEC’s Characterizing Uncertain Sea Level Rise Projections to Support Investment Decisions, Finance Guide for Resilient By Design,22 Transit Resiliency Funding Opportunities,23 and others all provide guidance, suggestions, and ideas to guide funding to support adaptation strategy implementation. Funding is a dynamic component of adaptation planning. Many of the foundational funding sources are familiar, such as general funds; others, such as new grant programs or green bond financing, emerge on an ongoing basis. Many of the websites and resources summarized in this section, particularly from the State of California, such as the Adaptation Clearinghouse, allow communities to track the emergence of these resources.

In cases where an adaptation strategy requires construction of a physical asset typically included in a capital investment plan, the asset can be included in the annual or biennial planning process, which are better equipped for financing larger projects. An effective way to support implementation—whether using the capital investment plan or local general fund—is to demonstrate the fiscal benefits from loss avoidance and improved public safety. It is almost always less costly to address climate impacts or hazards ahead of time rather than responding after they happen.

Step 4.2: Monitor

Climate conditions continually change, as do science, community characteristics, regulations, technology, and other factors that affect adaptation needs. Monitoring is critical to ensure that the chosen strategies to address community vulnerability continue to be as effective as planned. For each adaptation strategy, one department should be designated as the responsible agency for carrying out monitoring activities, including storing monitoring data. In many cases, this also requires designation of a dedicated funding source for monitoring activities. The responsible agency can be a jurisdictional department, regional entity such as a council of governments, or a community group. If a community group, a specific memorandum of understanding should be established between a jurisdictional department or regional entity and the community group to ensure ongoing data collection and data quality. There should also be a designated department that gathers and compiles all the monitoring data from all the monitoring entities to conduct an overall assessment of effectiveness.

Monitoring is the easiest and most cost-effective when using an indicator that is already collected as part of day-to-day operations. During strategy development and prioritization (Phase 3), the indicator to be monitored should be identified. It should reflect the impact being addressed, the desired outcome, and the specifics of the individual strategy. Identified indicators should be collected at a prespecified interval—at least annually, although more frequent collection rates may be necessary (such as event frequency or tide height). Example indicators include signals of the impact being addressed, such as beach width, mean high tide, flood frequency and peak flow, or fire frequency and intensity; the desired outcomes, such as asthma rates, days missed from work or school, air quality, or climate hazard losses; and specifics of the strategy, such as structural condition of mitigation or days and frequency of closure or service disruption (roads or other assets).

Monitoring and Outreach

The results of monitoring efforts should be reported regularly to the public to maintain awareness of effectiveness and local adaptation needs. Communities can publish a regular adaptation report to the public, place the information on an interactive website that is regularly updated, or report the results through other means. The cities of Encinitas, Burlingame, and Richmond all provide examples of municipal efforts for communicating implementation progress. This type of transparency is critical to keeping the community engaged in the ongoing challenge of adaptation. In particular, this data should be available and communicated to community members who are expected to be most susceptible to climate-related issues. Some sample actions are:

- Document lessons learned during the planning process and ensure that future planning processes take the lessons into consideration.

- Have a community advisory board lead monitoring and review of the plan, or partner with a university or college program to do this.

- Identify mechanisms for holding agencies and departments accountable.

- Use “open data” online platform approaches to sharing climate, project implementation, and equity information with community members.

Step 4.3: Evaluate

Strategies are evaluated because the increasing severity of climate change and changes in community characteristics cause continually changing levels of effectiveness. Monitoring is the first step in adjusting to these changes. The monitoring data should be analyzed and evaluated to identify if and how a strategy no longer meets community needs. This evaluation should focus on what the community sees as the goal of the adaptation strategy, so that effectiveness can be assessed based on community need. When a strategy is identified as losing effectiveness, a series of steps are needed to plot a path forward. State legislation may also trigger a re-evaluation of the vulnerability assessment and adaptation strategies.

When a strategy loses effectiveness, the vulnerability and susceptibility of the people, resources, assets, or operations it affects should be reassessed. It is most practical to keep the focus of the reassessment as narrow as possible—a new, comprehensive vulnerability assessment is not always necessary. When updating a vulnerability assessment—whether individual scores or the entire analysis—the first priority is to review any scientific updates and changes to community characteristics. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change updates its periodic summary of climate science and global adaptive needs every five to seven years.27 The state issues an updated Safeguarding California Plan periodically with updated science and state conditions, and conducts a new Climate Change Assessment every few years.28 There are also many regional assessments emerging from universities and regional agencies or nongovernmental entities. All these reports may have updated science and other useful information.

Another source for new or improved data is datasets or studies prepared in the aftermath of climate-exacerbated hazards, such as fire or flooding. These resources often combine local social conditions and context with bio-geophysical factors that contributed to the experienced hazard event.

As community planners know, community characteristics change over time. When an adaptation strategy loses effectiveness, it is critical to assess whether or not changes in the community have altered the experienced climate change effects, increased the vulnerability of any populations or assets, or made any additional community members or assets susceptible. For example, if a growing community has increased its level of development and associated impervious surfaces, it may have also increased its flood risk. The community should assess if the escalating risk disproportionately affects any specific populations or locations. County health departments are a key community ally in identifying changes to the population characteristics and to overall health indicators.

Evaluation and Outreach

Community outreach and education programs about evaluation can be a very effective way to engage community members in efforts to shift course in adaptation strategies. Include the public by, at a minimum, disclosing evaluation outcomes transparently. This leads to a better understanding of the finite nature of any single adaptation strategy. It is also possible to include community organizations or committees in the assessment and evaluation of monitoring data. More direct participation fosters better understanding across more of the community, and it should include disproportionately affected or frontline communities in these efforts. Some sample actions are:

- Define and regularly measure a series of equity-related indicators.

- Develop a reporting system (e.g., online) to communicate results for the equity-related indicators through time.

- Ensure clear avenues for recourse and accountability of project implementation.

Step 4.4: Adjust

Evaluation of monitoring data following measure implementation may reveal the need for adjustment, which could trigger the strengthening of a strategy or an entirely new approach to the vulnerability. Each strategy should be evaluated carefully to assess the extent to which it can be bolstered to address increasing impacts of climate change and the extent to which it precludes strategies that may more effectively address the impacts. Such assessments should take place during the first couple of years of implementation of any strategy so that potential strengthening and compatibility with other strategies are known from the outset, making for smoother adjustments based on indicator evaluation. For example, strengthening a sea wall or flood wall may make retreat or accommodation strategies more difficult to pursue; however, in many cases, initially bolstering a physical barrier can give a community time to set up strategies that accommodate higher sea or flood levels. Once those are in place, the physical barrier should give way to the accommodation strategy (see Table 13). Evaluation of monitoring data can help communities determine when such transitions should take place.

Strengthening a strategy varies widely by strategy, from changing the speed of implementation, to altering its location, to revising the implementation mechanism. The changes to strengthen a strategy should be identified as part of the initial implementation, and the indicator being monitored should be tied to pre-identified points where strengthening may be required.

As well as evaluating strategies for the extent to which they can be strengthened, they should be evaluated for their compatibility with potentially more effective strategies. In many cases the strategies that are potentially more effective take longer or cost more to implement, making them better suited to be a longer-term strategy that can be implemented after priority strategies are put into effect. Choosing when to shift to the longer-term strategy is more easily managed when specific triggers for the shift are identified ahead of time (see Table 13).

| Risk | Actions | Lead time | Adaptation Options< |

| Beach Erosion | Protect | 5–10 years | Beach and dune nourishment |

| 10–15 yrs | Raise and Improve sea walls | ||

| 15–20 yrs | Sand retention strategies | ||

| Accommodate | 5–10 yrs | Elevate structures | |

| Retreat | 15–20 yrs | Relocate public infrastructure | |

| Source: Environmental Science Associates, City of Del Mar Sea-Level Rise Adaptation Plan, prepared for the City of Del Mar, August 2016, updated May 2018, https://www.delmar.ca.us/DocumentCenter/View/3580/Revised-Adaptation-Plan-per-Council-May-21. | |||

Adjustment and Outreach

Communicating with the community and inviting its collaboration throughout the implementation process, both before and during adjustment, are critical to sustaining ongoing adaptation. A community should not be surprised by changes in approach, which should be communicated consistently as a normal part of long-term climate adaptation strategy implementation. Without appropriate inclusion of the community throughout the process, changing a strategy could be viewed as abandoning it or as a failure of implementation rather than as a successful outcome of good monitoring and evaluation. Sustained engagement with the community and transparency in monitoring and evaluation can help avoid such misunderstandings, which can lead to community dissatisfaction with adaptation actions. Additionally, community inclusion can supplement the selection process for the new or bolstered strategy.

Some sample actions are:

- Ensure that lessons learned and outcomes from review and monitoring of implementation are publicly available.

- Use data to inform plan updates and/or make any needed course corrections.

- Develop materials allowing for pop-up events to solicit feedback and ideas for strategy adjustment when needed.

- Collaborate with the community to update strategies and program implementation based on lessons learned from monitoring.

Phase 4 Wrap-Up

Adaptation planning work does not end when the plan is finalized. Communities must implement the plan, monitor and evaluate its effectiveness, and adjust the plan in response to feedback and changing conditions. It is important to determine funding, timing, and responsibility as part of this work. And as with all other phases of adaptation planning, community engagement is critical. Adaptation planning is a cyclical process, and the adjustment work in particular involves revisiting or redoing previous phases. With a robust and ongoing adaptation planning effort, communities position themselves to better resist a changing climate so that they can continue to thrive.